DISCOVER

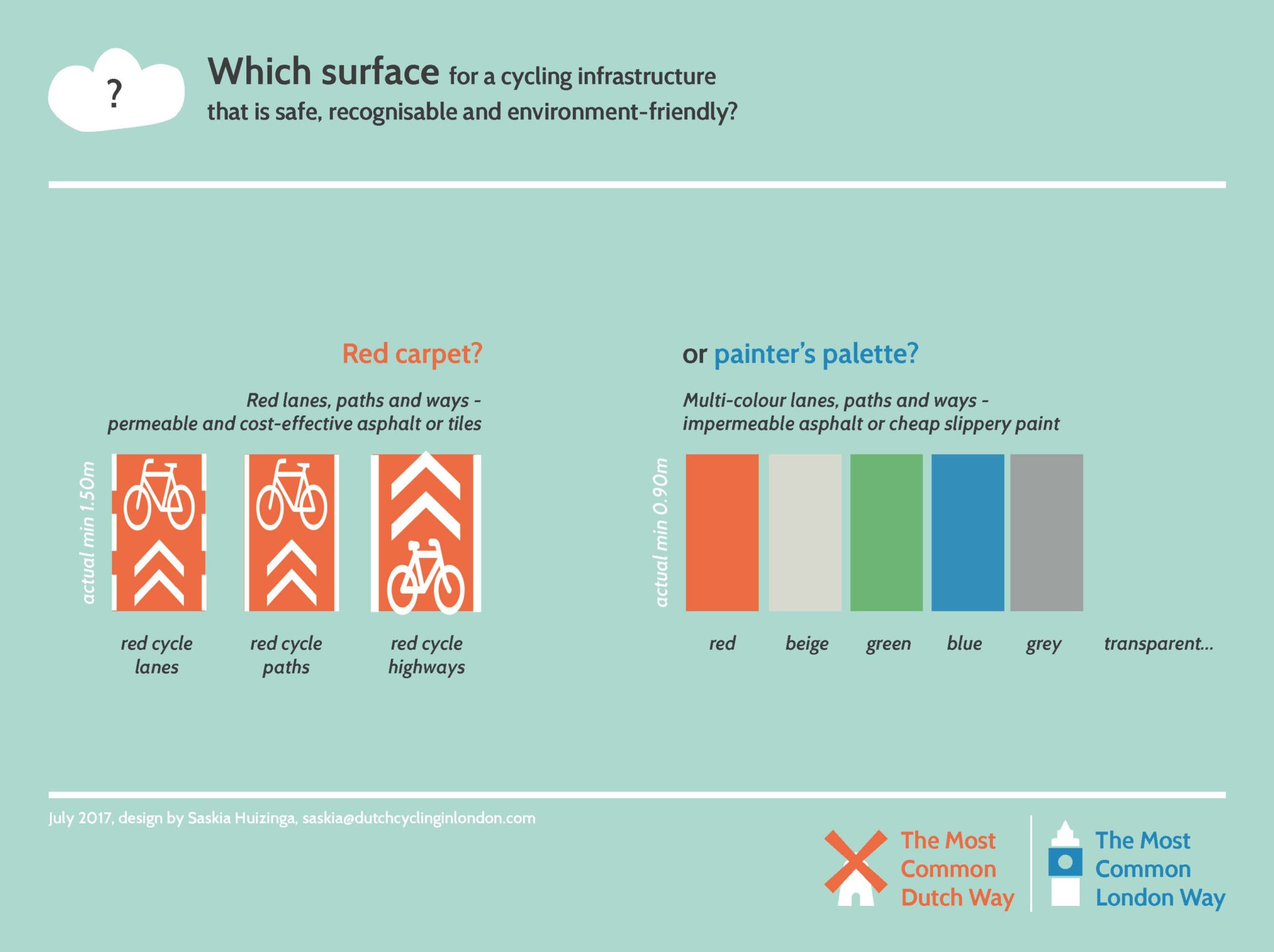

Which surface for a cycling infrastructure that is safe, recognisable and environment-friendly?

The Highway Code defines what markings and signs mean in the whole country. We couldn’t imagine a STOP sign being different from a borough to another one, could we?

Golden rule

CONSISTENCY. Human beings need common rules and codes to be able to function together and this is what the Highway Code is for with regards with infrastructure. What about something that is as important as marking lanes?

photo@fietschic

National standards

Just like in the UK, the Netherlands has no compulsory cycling standards. Nevertheless urban designers follow standards such as the ones developed by the CROW knowledge platform on infrastructure for two reasons.

- They have been tested and improved over 40 years.

- They are helping with consistency. Exactly as signs and markings are consistent through the whole UK and defined in the Highway Code, common Dutch street design standards are very much helpful for road users to quickly understand the functioning of a place, wherever it is in the Netherlands and even when it’s the first time they use it. It is a matter of safety.

Colour

For this reason, whenever it is necessary to protect cyclists from faster or bigger vehicles, and at all conflict points (such as junctions), paths, lanes and highways are coloured in red/orange. Why this colour?

- Economics. Red asphalt is the cheapest to get after the black one.

- Psychology. It is the colour that provokes the most response among humans.

- Visibility. It stands out well against backgrounds of black (asphalt) compare to blue or green.

- Harmony. Red is a common colour in nature and integrates well with Dutch/English buildings, mostly made of red clay bricks.

Width

Minimum width is 1.50m for a cycle lane and 2m for a protected cycle path, according to CROW’s Design Manual for Bicycle Traffic.

The right width can be the difference between a stressful adventure and a great cycling experience. That’s one of the differences that make so many Dutch people to pick the bike when they need to go somewhere. Wide and safe infrastructure is what brings the masses – and not only the fanatics – to cycle.

Surfacing

The Dutch do not use any paint for their cycling infrastructure. Paint might be cheaper than stones and asphalt but it is dangerous because it becomes slippery when it rains (unless it is especially made porous).

Shared, shopping and residential streets are often made of bricks or stones set on sand because these are encouraging motorised vehicles to slow down and are made of more sustainable and local materials (no petrol involved). But bike lanes, paths and highways are usually made of asphalt as this material is smoother and allows cyclists to go faster.

Both are made permeable which allows water to pass freely through to the underlying structure. Why is that important?

- Just as the UK, the Netherlands is country where it rains a lot. Flooded roads and puddles are very dangerous as cyclists can slip and lose control. Cyclists are also getting wetter than they should be.

- By canalising water towards sewers instead of letting water drain through the pavement surface and infiltrate into the soils below the pavement, we prevent phreatic zones to refill and plants nearby to be watered. There are a number of cases of floor collapsing because of empty phreatic zones.

- Through running on the road before entering sewers, water gets polluted by catching all dirt and oil that sits on the road. In addition to reducing runoff, permeable asphalt effectively traps suspended solids and filters pollutants from the water.

- Porous asphalt decreases urban heat islands (UHI) because water that directly drains through the asphalt makes roads cooler. UHI are due to the amount of hard surfaces and the lack of plants and shade in urban areas. They decrease air quality by increasing the production of pollutants such as ozone, and decrease water quality as warmer waters flow into area streams and put stress on their ecosystems.

- Porous asphalt has an inverted texture that allows for high capacity acoustic absorption, which is much needed in dense urban areas such as in the Netherlands or London.

Sign up to our newsletter

A project supported

by the Academy of Urbanism

A project initiated

by Saskia Huizinga